Last week we had a distressed email from one of our clients, a Holiday Inn Express off a motorway in England. Since October 2014, their direct bookings (the ones that come through their own website as opposed to their property’s IHG landing page on hiexpress.com) had dropped by 40%. Meanwhile, the bookings going through their IHG landing page had gone up by 35%. It looked, for all intents and purposes, like IHG had somehow managed to steal nearly a third of the hotel website’s traffic away and onto the hiexpress.com portal. But how?

The short answer: Google Places. But before getting into that, it’s important to understand why this is actually a problem. After all, signing up to a brand franchise surely means you’re expecting them to do all your marketing for you anyway – especially if you’re paying them a percentage of gross revenue (as is often the case). So why does it matter if the bookings are going directly through the Brand.com page instead of via your website first? They all end up in the same central reservation system in the end.

Put simply, it matters because being part of a brand can be very expensive, all told. Franchise fees, marketing fees, training fees, booking fees, loyalty programme fees, and various other fees all add up to a large cost of sale for each booking. Because of this, plus the various rules related to rate strategy which you have to adhere to as part of the brand, you end up in a situation where your margins are squeezed to within an inch of their lives. Unless the brand is delivering 100% occupancy on a consistent basis (let’s be realistic now), you need to care about direct marketing efforts to have any chance of decent profitability.

A brand, meanwhile, is constantly under pressure to prove that these large fees are worthwhile, so the last thing it wants is for your marketing efforts to be more effective than its own. It’s a curious kind of tension that runs through most brand/franchisee relationships, and your impact on revenue contribution can become a significant factor when it comes to negotiating your franchise agreement.

You scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours

The biggest weapon a brand has is its size, and one of the biggest benefits to becoming a franchisee is not only the marketing reach a brand has but also the more favourable rates it can negotiate with OTAs such as Booking.com. When you go it alone on OTAs you find yourself paying for position on the search results, which in some cases can lead to your commission rates being pushed up as high as 40%! As a brand, however, you will more likely be paying around 15% commission. Theoretically then, far more favourable to be part of a brand.

Is it healthy for the competitive landscape though? Having to be part of a brand in order to access those more reasonable lower commission rates on OTAs might seem like an unnecessary lock-in. And when you consider that it is you, as the hotel, who carries the 15% fee on every OTA booking on top of the fee paid to your brand – effectively paying two sets of commission on each OTA booking – the faintest whiff of raw deal emerges. As I mentioned previously, your leverage in franchise agreement negotiations is critical, but on the OTA front you’re effectively unable to compete with your brand. To the uninitiated, it might even look like OTAs and brands are colluding to shut out independents, though the reality is more economics than politics (OTAs hurt hotels in other ways, but that’s a different topic).

Bottom line though: brands get favourable listings on OTAs compared to independents, and OTAs make it very hard to compete with that. So your direct marketing efforts need to be directed elsewhere.

Don’t be evil

Enter Google, a company whose mission statement is “you can make money without doing evil“. Evil is of course a highly subjective concept, but the underlying value being promoted here is transparency. Google has always publicly been against opaque business practices that skew the democratic landscape of the web, more specifically anything that benefits the “big dogs” over everyone else. By that definition, the OTA/Brand commission rate collusion could be considered evil, whereas Google has always been the playing field where anybody has a shot, as long as the rules of capitalism are followed.

Case in point: Adwords, Google’s auction-based advertising platform where companies bid against each other for specific keywords. This is a completely transparent system, as although it is highly likely you will be outbid by the aforementioned “big dogs” on the most popular keywords, you do at least have the opportunity to play with them on the same field. Of course, being a fundamentally capitalist system, the larger companies do tend to swing towards anti-competitive practices sooner or later. In the case of OTAs, they bid against you for your own brand keywords, ensuring the OTA page for your hotel outranks even your Brand.com page. Following close behind them (and increasingly now ahead of them), your brand uses the money you pay them to make sure the Brand.com page outranks the direct website. So even if you wanted to compete for your own keywords, you would only be driving the price up for others using your own money to outbid you.

All of which is a bit unfair, bordering unethical, but at least is transparent: we can all see it going on. But then Google introduced Hotel Finder, and everything changed.

The OTA killer?

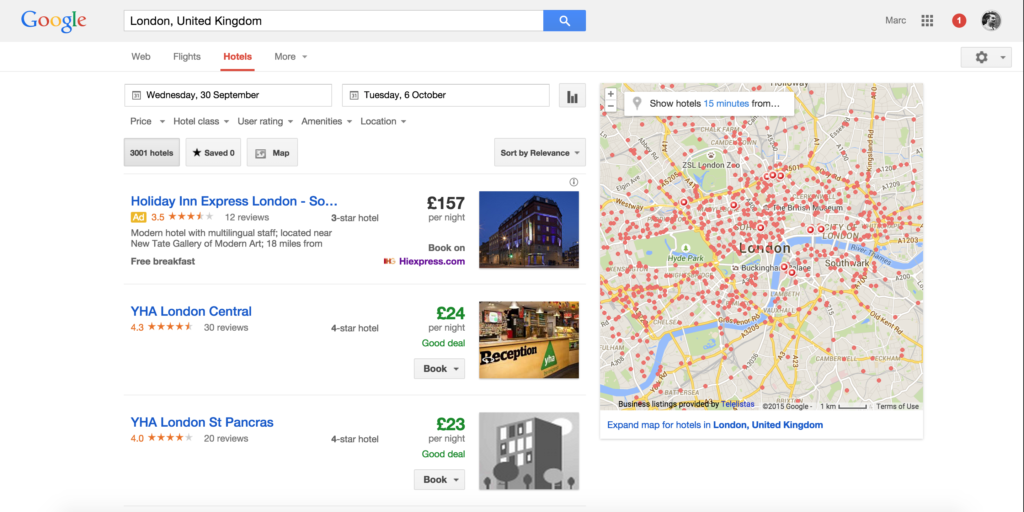

Hotel Finder is Google’s initiative to make it easier for people to find and book hotels directly from the search engine. It looks a lot like an OTA, and behaves a lot like an OTA. A quick search for hotels in London gives a Holiday Inn Express as top result.

Is this Booking.com? Nope, it’s Google.

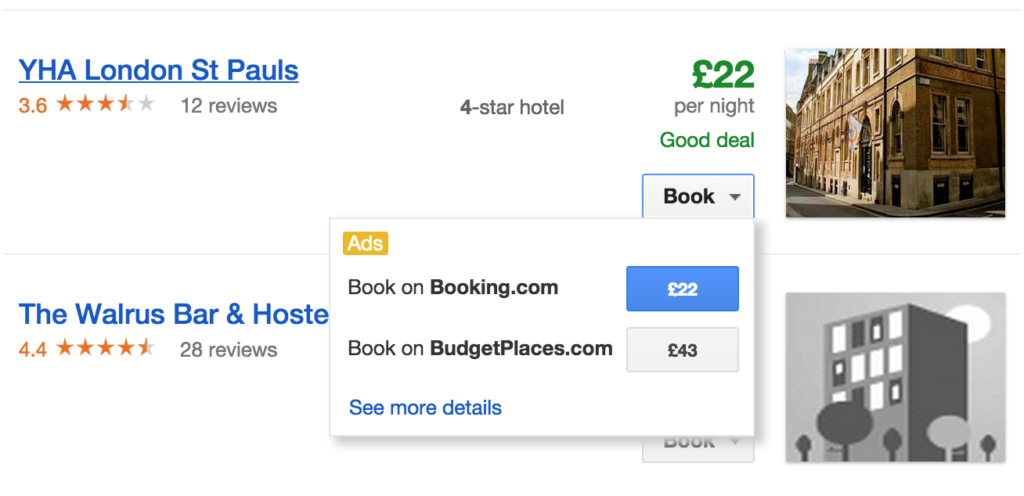

You might be thinking “okay, but that top result is obviously an advert (it says so in bold yellow)”, so what of the hotel and hostel results that follow? Well, click on the enticing “Book” button and here’s what you get:

Oh look, it’s those pesky OTAs again.

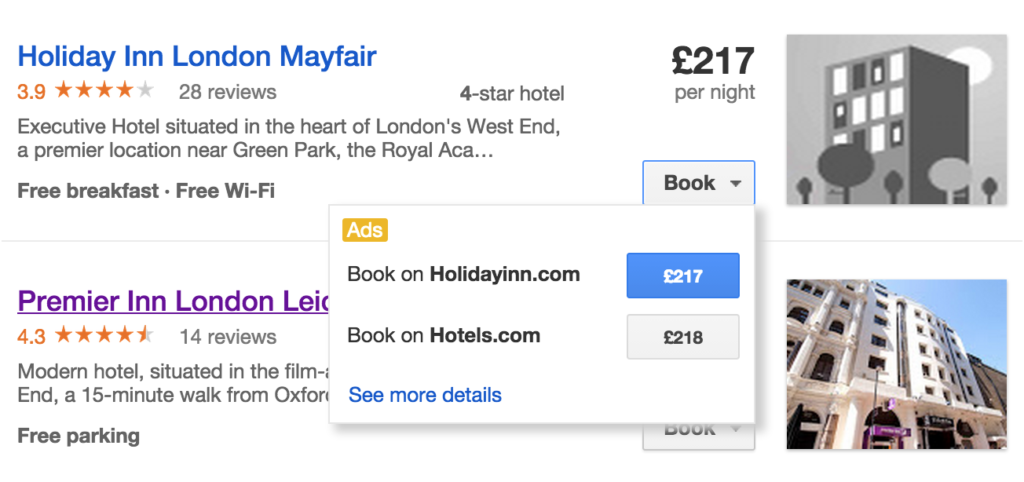

If you’re part of a brand, you will get the Brand.com page as well as an OTA page:

Hm, choices…

But where oh where is the direct website option for any of these hotels? And how do the brands and OTAs get their prices onto Google Hotel Finder in the first place? I’ll get onto that, but first we need to talk about Google Maps, because this is where the real damage is being done.

Location is everything

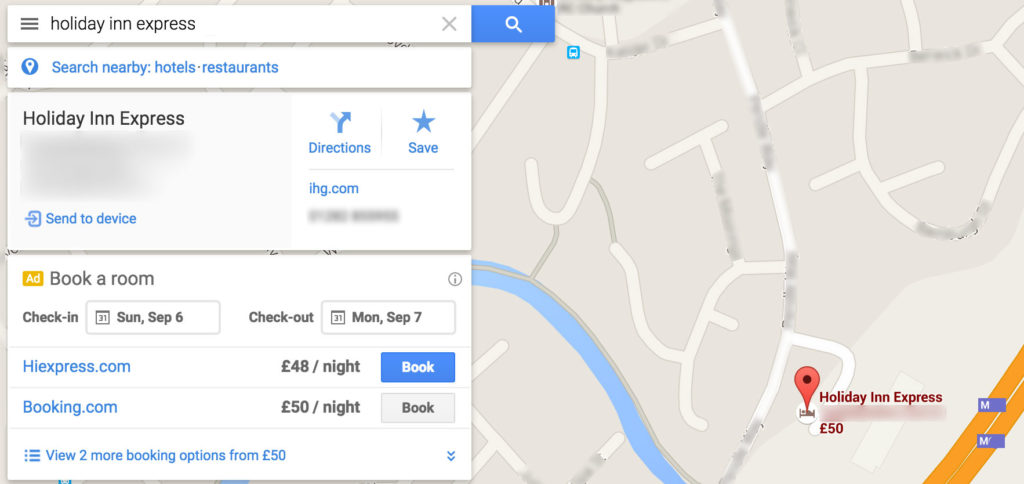

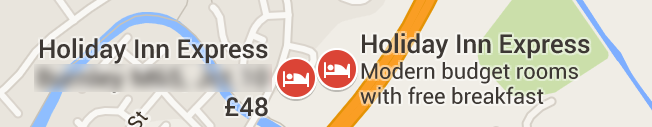

Let’s go back to our distressed client from the opening paragraph. You may recall they had a motorway hotel with the Holiday Inn Express brand on it, and common sense will suggest that Google Maps is likely to be a key source of discovery for guests of that hotel – for motorway hotels, location is key. Here is what comes up when you search for the hotel on Google Maps:

Details have been blurred to protect client’s identity.

This result looks great. A clear direct hit on the map pin, showing me exactly where the hotel is (and on which side of the motorway); address details and directions button on the left-hand side (the latter being convertible to GPS directions if we’re using a phone); some detail and photos about the hotel and a big friendly booking box in the middle, which is pulled in from Hotel Finder (aha! That’s why it matters). For a potential guest, this is a great user experience. Well done Google.

But wait! When we click the “Search nearby hotels” link, then zoom back in a couple of notches, suddenly there are two pins for the Holiday Inn Express at this location:

Well, this is awkward…

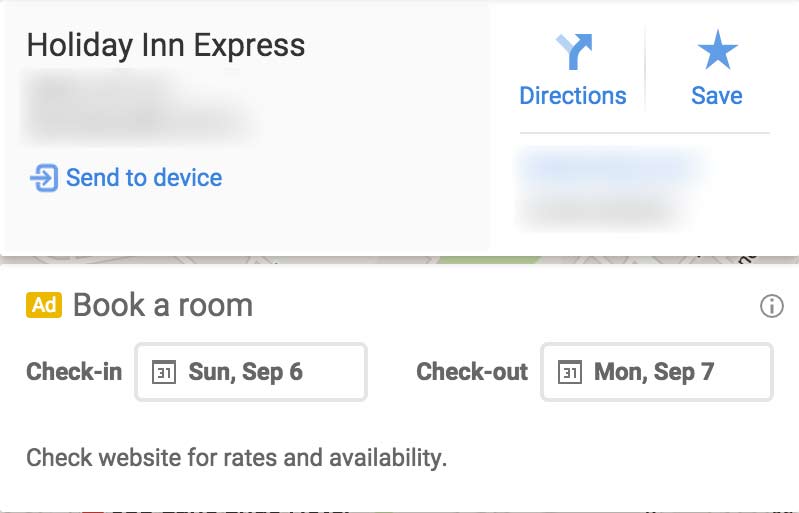

Before you suggest it, no: IHG did not decide to have two Holiday Inn Express franchises right next to each other. Each pin represents a separate Google Places page (essentially Google’s version of the Yellow Pages and where Google pulls its information from when it shows your business on Google Maps): the one on the left is owned and managed by IHG, while the one on the right is owned and managed by the hotel itself. Notice that only the IHG pin has a price under it. Clicking on the other pin, owned by the hotel itself, we get this:

And how do I book?

Notice the “Book a room” box this time, and the death-knell sentence that sits in place of the shiny “Book” buttons visible on IHG’s listing:

Check website for rates and availability.

Assuming the user has even got as far as finding this listing instead of the IHG one (and let’s face it, that’s unlikely considering the IHG pin pops up first), being told to go elsewhere to find rates is quite frankly akin to telling them to bugger off.

Which leads on to the previously-posed question: how do the brands and OTAs get their rates onto Google’s Hotel Finder… and more importantly, how do you?

The answer to the latter question is easy: you can’t put your rates on Hotel Finder. Only OTAs and hotels with GDS-connected reservation systems can, which means that as a brand franchisee, where the reservation system is controlled by your brand, you’re totally locked out. Brands, meanwhile, enjoy a more prominent listing on Google Maps and Hotel Finder because Google favours search results with rates, layered with Adwords spend as a secondary dimension to really make sure you don’t stand a chance.

It ultimately means that your ability to compete on Google is significantly affected by the brands in the same way as your ability to compete on OTAs is. If you’re not with the big boys, you’re effectively shut out. Evil? By Google’s definition, it comes close.

Pigeon fanciers

This all started with the rollout of a major Google algorithm update code-named Google Pigeon:

Google Pigeon is a codename that refers to an algorithm update for Google’s Local Search search engine, which the company rolled out with the purpose of “providing a more useful and relevant experience for searchers seeking local results,”

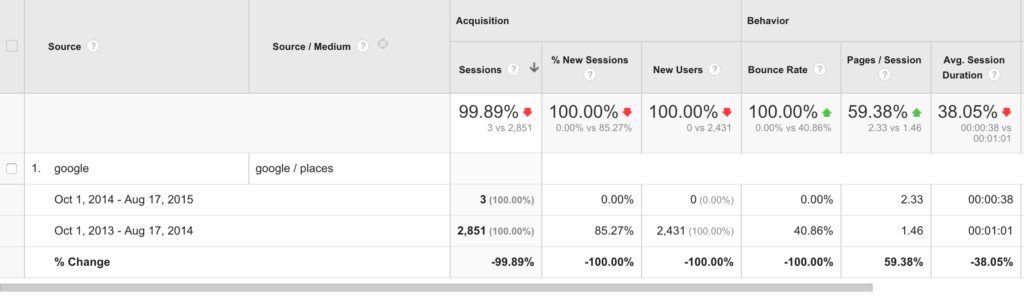

This update affected Google Maps more than anything, as that is of course where Local Search is focused. Google Pigeon was originally rolled out in June 2014 but didn’t hit the UK until – guess when – October 2014… right around the time that our client’s website traffic started to drop dramatically. So being the diligent data-driven detectives that we are, we looked into their Google Analytics and, after drilling down quite a bit to find the relevant data, found a damning piece of evidence:

This image speaks for itself. CLICK TO ENLARGE

In short: a 99.89% drop in referral traffic from Google Places (aka Google Maps) in the 10 months between October 2014 and August 2015 compared to the same period in the previous year.

I will let that sink in for a moment.

It’s important to understand that Google serves its end users first and foremost. They feel that the changes they’ve made provide a better user experience and to some extent that’s absolutely true. But what if the hotel’s direct website offers an even better user experience than the IHG landing pages? That has suddenly become an irrelevance because it will now probably never be seen on the search engine. Worst of all, it has allowed the OTAs and brands to strengthen their grip on online hotel inventory in a way that totally throttles competition. Now that’s definitely evil.

So, what can be done?

As I mentioned earlier, direct marketing is an essential piece of your revenue strategy even if you are a brand franchisee. But where hotels have become depressingly used to being given a raw deal by the OTAs, this is the first time that Google has really joined in on the act. Ironically, the GDS/OTA lock-in means that you are actually in a better position to compete as an independent, as you at least have the option to adopt a GDS-connected reservation system and go toe-to-toe with the big boys. Plus of course, you will only have the OTAs bidding against your brand keywords, not the brands as well.

For brand franchisees however, I can only recommend that you give up on Google for now, and concentrate your marketing efforts elsewhere.

The good news is that there are a lot of other channels you can direct your marketing energies towards, and we have been seeing increasingly good returns from our work with hotels on social media, content marketing, local activity and strategic leveraging of analytics data. The brands and OTAs are all weak on this front and will likely remain so until they figure out a way to plant a representative into every hotel (never say never…).

If all else fails, there’s always Bing. With between 20-30% of the search engine market share nowadays, it’s not only becoming a significant search engine at last but is also a less competitive one. Our client hotel does very well on Bing currently, outranking both Tripadvisor and Booking.com as the number 1 search result for its brand keywords. Sadly Bing just doesn’t get the volume of traffic that Google does.

Perhaps if we all jump on the Bing bandwagon that will change, and Google will get the message.